Brooklyn Rail Farewell Transmission

by: Hovey Brock

In Farewell Transmission, May 2nd – July 1st, 2017, Roxy Paine’s first show with Paul Kasmin, his obsession with the accelerating turmoil of man-made entropy, otherwise known as climate change, assures his place as one of our most intelligent and sardonic sculptors of the Anthropocene. In this powerful multi-part exhibition, he takes us one step beyond the devastating effects of climate change, linking our socially destructive attempts to control people’s inner lives with the anthropogenic disruptions of the environment. Never with such force does Paine claim the personal is political is ecological.

Farewell Transmission spans two adjacent galleries in Chelsea. The first, a storefront space at 297 10th Avenue, features eight miniature Dendroids, his signature fictional tree constructions in which the natural branching structure of the tree draws together psychology, physiology, the climate, and other complex systems. Neuron Flower Tree, 2016, is an idealized representation of a neuron, with its axon as the trunk and the dendrites for the branches. Although from a completely different frame of reference, the neurological as apposed to the botanical, its morphology matches with uncanny precision the other tree sculptures in the room. Paine draws here, as he has elsewhere, a continuum of delicate dependencies between different scales in nature. After the Flood, 2016, shows a tree with an electric pole, clothing, and other detritus left behind from a surge of high water—a clear reference to the disturbances of the water cycle caused by climate change. On a more whimsical note, Mental State no. 5, 2017, and Coil (Mental State no. 4), 2017, attempt to illustrate what moods look like: perhaps the pimples and uneven bulges of no. 5 refer to irritation, while no. 4, with its teetering loops, suggests an obsessive thought turned over and over again in the mind.

But it is when moving across the street to the larger 293 10th Avenue space that Paine most forcefully makes the connection between the personal, the political, and the environmental. The two dioramas Experiment, 2015, and Meeting, 2015, and the installation Desolation Row, 2016, belong in a Museum of Unnatural History dedicated to the toxic biome of poisoned interpersonal relations. Each piece dissects the blowback?/residue of our failed attempts at imposing social and/or political constraints. The dioramas convey their messages literally, while the installation uses the language of metaphor.

The diorama experiment refers to a CIA project, which lasted from the 50s to the 70s, in which prostitutes were used to dose unwitting johns with LSD, in order to take them back to bedrooms equipped with one-way mirrors behind which CIA agents would observe the behavior of the johns under the influence. The goal of the research was to investigate whether the use of psychotropics was a viable form of anti-personnel weaponry. Built into the gallery wall, Paine’s diorama divides front to back in two parts. The observation room behind the mirror is closest to us. It is all in grey, equipped with a table, chairs, a telephone, a file cabinet, a toilet, and what appear to be wine glasses, as if the CIA agents were celebrating. Beyond it is the bedroom, which is colored in saffron, with a disheveled king-sized bed, a door to a bathroom, a knocked-over chair, and a pair of crumpled pants heaped on the floor. All the furniture is flattened, exaggerating the bleak emotional tenor of the space.

The second diorama, Meeting, shows a large office space with a circle of chairs, suggesting the setting for a twelve-step recovery group. A whiteboard on the right wall has hand-written inspirational captions about “captives,” “fugitives,” “unpromising hero,” “child rescued,” and numerous references to “demonic” forces at work: all labels suggesting a psychic habitat of dependency, persecution, guilt, and alienation. The presence of soft drinks and the ubiquitous institutional coffee urn on a table creates an air of something happening just off-stage, not unlike the unsettled bedroom in experiment. Yet, while experiment alludes to the covert, seemingly fantastic experiments of the CIA, Meeting is about the more familiar quotidian forms of self-help used as modes of social control. Paine’s point is these forms of social control, whether masked as covert government research or interpersonal cure, amount to a kind of societal autoimmune disease where the body politic, so to say, begins to attack itself.

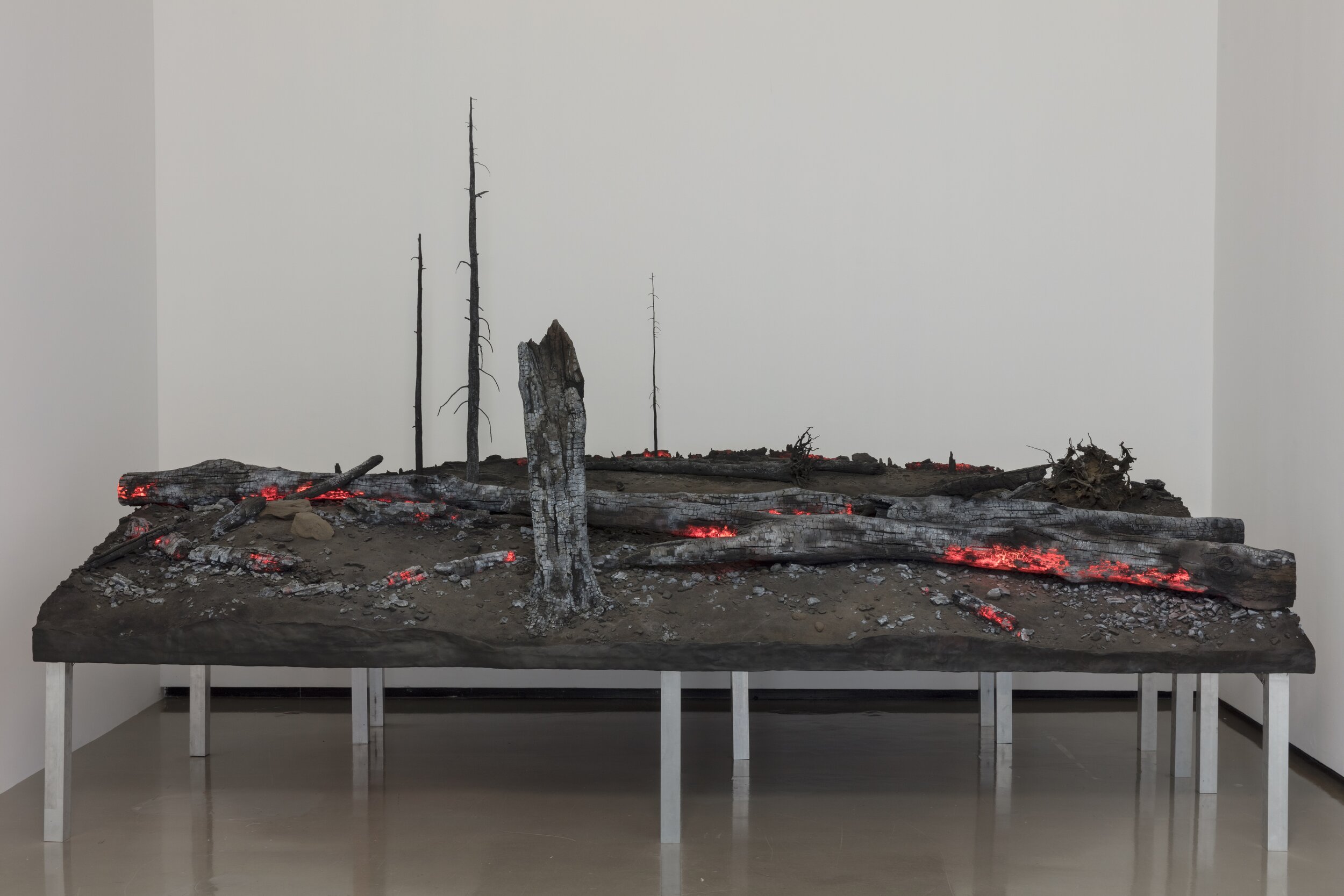

Bringing together the twin themes of compromised systems in nature and self-inflicted social trauma, the installation Desolation Row delivers a powerful statement on how they are related and the consequences of the damage done. It is indeed the capstone of the show, launching a stinging condemnation of the havoc caused by our deluded attempts at imposing our will on societal and environmental forces. In a darkened room, a platform against the wall has charred logs, parts of which are still glowing embers, strewn across a blackened ground. Here Paine literalizes a number of clichés: “burn out”, “scorched earth policies”, and, mordantly, the charred wasteland of global warming run rampant. Unhappily, the age of Trump has only substantiated Paine’s theme of wanton destruction, such as the United State’s abandonment of the Paris Agreement. On the political side, the governmental dysfunction has reached such a pitch that the slogan on both the extreme right and left of this country is now “Burn it all down.” Desolation Row rings out as a Cassandra-like cry from the heart that we are well on our way to doing so.